Birmingham’s Oldest Charity

Tudor Birmingham: Echoing to the Sound of Anvils

Founded in 1525, Lench’s Trust is one of the few constants in the succeeding five centuries of dramatic change propelling Birmingham from a small market and manufacturing town into one of the world’s greatest industrial centres. Throughout that extraordinary transformation, the Trustees adapted and innovated to meet the needs of less fortunate citizens. Started in the midst of Henry VIII’s tumultuous reign by William Lenche’s donation of land for charitable purposes, his Trust’s income was initially devoted to repairing bridges and roads locally, with the residue given to the poor. From the seventeenth century, the provision of almshouses became an increasingly important feature of the Lench’s Trust and by 1881, with its street-repairing functions long gone, it was focused on giving homes and pensions to necessitous women of the ‘deserving’ poor. No longer restrictive in its approach but proudly inclusive, today the Lench’s Trust continues to be a vital force for good in a post-industrial context with its provision of superior sheltered accommodation for up to 200 older people in need.

Yet for all the longevity and importance of the Trust he founded, William Lenche himself remains a mysterious figure, whilst the town he lived in was just beginning to emerge from obscurity. Contrary to popular beliefs, Birmingham is not a phenomenon of the modern world, instead it has deep roots. Yet though people have lived within its bounds for thousands of years, they are anonymous until the tumultuous Dark Ages. Then, around the time of the spectacular Staffordshire Hoard in the mid-600s, the first name appears: Beorma. He and his ingas, folk, founded a ham, a homestead – Beorma ingas ham becoming Birmingham. Though this leader’s name is all we know of him, it indicates that he and his group were Angles, an immigrant Germanic people from the Jutland Peninsula who gave their name to England and who were moving westwards from their original conquests in East Anglia.

Despite the apparent importance of Beorma founding one of the earliest Anglo-Saxon settlements in the West Midlands, it didn’t come into view until its first recorded mention in the Domesday Book of 1086. Revealed as an insignificant agricultural settlement, it had no obvious distinguishing characteristics or potential for growth. Landlocked and with no navigable river, it was not a defensive site and nor did it boast either iron ore or coal beneath its surface. Valued at merely 20 shillings, much less than the adjoining bigger manor of Aston, it had nine peasant tenants, giving a population of no more than 50. Yet, 80 years later, in 1166, the story of Birmingham’s emergence as a great city began when the Norman lord of the manor obtained a royal charter to hold a weekly market at his ‘castle’, a fortified manor house, on the edge of the modern Bull Ring. A new town quickly developed, with migrants from its rural hinterland attracted by its relative freedoms. Wanting to make money from tolls on traders and rents from tenants, Birmingham’s lord held a light touch, whilst there was no powerful bishop seeking his share, and no guilds of highly-skilled craftsmen stifling competition.

The Old Crown in the late 1860s, the mansion house of timber described by John

Leland in 1538. Built in the late fifteenth century, it would have been familiar to

William Lenche.

By about 1330, it’s probable that Birmingham’s population was close to 1,000 and though nowhere near as big as Coventry, it was a more important market town than others nearby. Its more prosperous citizens featured in tax records, yet nobody described Birmingham until 1538 when the traveller John Leland arrived. Coming down Camp Hill, he reached “as pretty a street or ever I entrd” – Deritend High Street, or ‘Dirtey’ as he called it:

“In it dwell smithes and cutlers, and there is a brooke (the River Rea) that divideth this street from Birmingham, and is an Hamlett, or member belonginge to the Parish therebye (Aston).

There is at the end of Dirtey a proper chappell (St. John’s) and mansion house of tymber (the ‘Old Crown’ pub), hard on the ripe (bank), as the brooke runneth downe; and as I went through the ford by the bridge, the water ran downe on the right hande (later Floodgate Street) and a few miles lower goeth into Tame, ripa dextra (by the right bank). This brooke riseth, as some say, four or five miles above Bermingham, towards Black Hilles (Waseley Hills).

The beauty of Bermingham, a good market down in the extreame (border) parts of Warwickshire, is one street (Digbeth), going up alonge almost from the left ripe (bank) of the brooke, up on the meane (modest) hill by the length of a quarter of a mile. I saw but one parish church (St. Martin’s). There be many smiths in the towne that use to make knives and all mannour of cuttinge tooles, and many loriners that make bittes, and a great many naylors. Soe that a great part of the town is maintained by smithes, who have their iron and sea-cole out of Staffordshire.”

A Deritend shoeing forge from a

sketch made in 1863, one of the many

smiths whose predecessors so grabbed

the attention of sixteenth-century

visitors with their clashing of metal.

Almost 50 years later, William Camden formed a similar impression: ‘Bermincham’ was a town, “swarming with inhabitants, and echoing with the noise of anvils, (for here are great numbers of smiths)”. Still, for all that it was the din of hammers and the clanging of metal that struck visitors, Birmingham boasted a wide range of occupations. Amongst them were unskilled labourers, butchers, innkeepers, millers, tailors, carpenters, coopers, bakers, and sellers of hot food, ironware, rope, cloth, and shoes. Most of these didn’t pay taxes, unlike the 156 names recorded for the Lay Subsidy of 1524-25 levied on land and goods over certain amounts. Craftsmen like smiths, loriners, nailors, and weavers and even a servant made up 91% of the taxpayers. However, the overwhelming majority paid only a little and together, they owned merely 50% of the town’s wealth. The other half belonged to the elite 9% of taxpayers. Of these, the highest payers were landholders: the lord of the manor, two religious guilds; and two men.

Then came eight men whose rates were based on their goods. They were headed by John Lenche and John Shilton, each with an assessment of 40 shillings. A first cousin of William Lenche, John Lenche was probably one of the two graziers renting land for grazing cattle, whilst Shilton was a mercer, a merchant trading in many things but especially spices and materials for clothing. He would be the first named of William Lenche’s 19 friends and associates in the Deed of Enfeoffment, the Deed of Gift setting up his trust. Of the other leading taxpayers in 1524-25, the lawyer Humphrey Symonds was one of the two executors of Lenche’s will; two were ironmongers supplying the metal to craft workers and buying back their wares to sell on; one was a scythe smith working in a highly-specialised trade; and the last was a tanner, preserving and transforming animal hides into the leather that was vital for the making of so many goods in Tudor England. That tanner was Roger Foxall, one of the four supervisors of Lenche’s will and it was as a tanner, grazier, and butcher that William Lenche waxed wealthy.

William Lenche of Birmingham

The first of his name relating to Birmingham was John de Lenche, noted in a legal document from 1262 concerning the lord of the manor. This was a period when people other than barons and knights were adopting hereditary surnames, a trend especially noticeable amongst merchants, craftsmen, traders, and the prosperous in general. Significantly, last names connected to places provide direct evidence of migration to mediaeval towns because those incomers were identified by whence they came. So, John was of (de) Lenche, hailing from the Vale of Evesham in Worcestershire where there are five villages so called. His type of surname was common in late thirteenth-century Birmingham, with most connected to places now within the city’s boundaries or within a 10 mile radius of its centre. However, the pull of the town was shown by a considerable proportion of migrants coming from further west in Staffordshire and Worcestershire, with the Lench villages over 30 miles distant.

It wouldn’t seem that de Lenche was pushed to move by poverty as his family were the lords of the manor of what became Rouse Lench. Instead, it’s likely that he was a younger son seeking to make his own mark. If so, he did just that as the 1262 source also gives him as a juror at the Warwickshire Eyre, a temporary law court with justices sent out from the central courts in Westminster. Jurors like him were freeholders and usually the leading men in their district. In Lenche’s case, this was the Hemlingford Hundred part of the county, covering modern Birmingham, Coventry, Solihull, and much of North Warwickshire.

With no one called Lenche mentioned in the Borough Rentals of 1296 and 1344-45 for Birmingham itself, it seems that John de Lenche was a property owner in Aston, as in 1346, a Robert de Lenche was mentioned in a land document relating to that large and then separate manor. Fifty years later, a William Lenche was recorded as of Duddeston, another manor that would also become part of Birmingham. It’s apparent that the Lenche family extended its holdings as the 1471 will of another William noted lands and tenements (buildings) in Saltley, Bordesley, Nechells, Little Bromwich, and Handsworth – all then outside Birmingham.

William’s son, John, did even better, going on to own property in Birmingham, where he became a leading citizen. In 1451, he and his wife, Isabella, were registered as members of the prestigious Guild of St. Anne of Knowle. Then in 1483, he was given as of ‘Dereyatyende’ (Deritend), Birmingham’s first suburb, although it was in Aston when he became Master of the Guild of the Holy Cross of Birmingham.

The Guild of the Holy Cross also doled out money to the poor of Birmingham,

something that Lench’s Trust would take on after the dissolution of the Guild under

Henry VIII. This depiction of the Distribution of the Dole by Kate E. Bunce is one of

several panels in Birmingham’s Town Hall. A prominent artist associated with the

Arts and Craft Movement, she was one of several artists commissioned to show

important aspects of the city’s past. The significance of Lench’s is emphasised by

another mural by Bunce illustrating its almshouses.

Birmingham. This was the most prominent position in the town. A religious guild founded for the parish church of St. Martin’s, it was endowed with property and land by wealthy worshippers. Most of its rental income was spent on maintaining three chaplains to say masses for the souls of dead guild members, both men and women, and on an organist. The remainder went on maintaining the two bridges over the River Rea at Deritend and paying for a common midwife and almshouses for 12 aged brethren. As well as the chantry in St. Martin’s, there was a guildhall on New Street, later the site of King Edward’s School and now of the Odeon Cinema. The Guild itself was overseen by a master and wardens, all drawn from the most successful men in Birmingham such as John Lenche.

As noted in 1487, his brother, Henry Lenche of ‘Byrmyngeham’, was the father of William Lenche who endowed the Trust. Deeming himself also of Birmingham, William was obviously an astute businessman making his money through interconnected enterprises which he controlled: buying and grazing cattle; butchering them and selling the meat; and tanning their hides for leather workers.

By the turn of the fifteenth century, Birmingham was a cattle market of regional importance. However, its town was small, huddled around a small space in the Bull Ring and stretching downhill along Digbeth to Deritend. Consequently, most of the manor remained open land in what was called the foreign. This stretched from Smethwick (Cape Hill) in the west to Gosta Green (Aston University) and the bounds of Aston in the east, and from Hockley Brook, the dividing line with Handsworth to the north, and the borders with Kings Norton and Edgbaston in the south (the Middle Ring Road). Much of this area was the lord’s own holdings, whilst a sizeable portion was heath (Winson Green). Most of the rest was better suited for animal husbandry rather than arable farming. This grassland for grazing cattle and sheep covered the modern Attwood Green, Ladywood, the Jewellery Quarter, and Hockley.

The cattle trade grew greatly throughout the 1400s and by the Tudor period, drovers from Brecon and Radnorshire in Wales were fetching their stock to Birmingham and selling it at the Welsh Market at the start of the High Street. Graziers bought the animals to fatten them up and either sell them on or have them slaughtered. The Survey of Birmingham in 1553 mentioned about 80 pastures for grazing. These were held by 20 men of substance, several of whom were wealthy graziers dealing in cattle at both the English and Welsh markets.

A generation before, William Lenche was one of them and like others, he sold meat, as in 1520 he was called a ‘bocher’, butcher. He would have employed someone to do so in The Shambles, that part of the Bull Ring where the butchers gathered. This was probably his servant, William Paynton, who was later recorded as having a shop there and, elsewhere, also leasing houses with crops, barns, and pastures from Lenche’s widow.

As had been done for centuries, a drover is driving cattle to the market in the Bull

Ring in the early 1800s. In the foreground is the English Cross and in the background

is St. Martin’s Church. Between them is The Shambles where Lenche would have had

his butcher’s shop. The Cross and buildings in The Shambles were soon to be cleared

to open the Bull Ring, leaving the church at the base of a wide space.

Significantly, Paynton was appointed a feoffee by Lenche in his Deed of Gift and went on to become a wealthy man. In his 1555 will, Paynton left sheep to various relatives, suggesting that both men also dealt in wool and hence cloth.

Woollen manufacture, however, was declining in Birmingham. By contrast, the leather industry was flourishing, so much that it was a staple industry of the town. With no great manufacture of soft tawed leather like gloves and purses or of tanned leather such as shoes, Birmingham specialised in the primary process of tanning. The 1553 survey of the town noted tanneries along Tanners Row, by the modern Mill Lane and Digbeth Coach Station. Located on low-lying ground, they took water from a stream running down to the Rea, across from which was a tannery on Deritend Island. Formed by what then were two courses of the river, it’s now the site of South and City College. Copious amounts of water were essential for tanning, a dirty, stinking, noxious trade pushed to the outskirts of any built-up area.

Cattle hides were brought to the tanners from the skinners with the tails, heads, and horns still attached. After they were removed, the horns were used to make knife handles and other items, whilst the trimmed and stiff skins were cured with salt to stop bacteria growing. Then they were cast into a pit of clean water to take away the blood and gore and to soften them. Once ready, they were pulled out and pounded to get rid of the remaining fat and flesh. Next, the hair was loosened in one of three ways: the hides were coated with an alkaline lime mixture; soaked in vats of urine; or left out for months to putrefy. After that, they were dipped in a solution of salt to remove any water and the tanner scudded the hide, scraping off the hair with a dull knife. This was followed by puering, softening the hides to make them supple, achieved either by soaking in a solution of animal brains or bating (beaten) with sticks with animal dung, usually of dogs or pigeons.

With the preparatory stages completed, the tanning began using tannin, a chemical compound derived from certain plant leaves but mostly oak tree bark. This was ground and left to stand with water in leeching pits, with the longer it stood the stronger the ‘liquor’. The hides were stretched out on frames and immersed in vats of the liquor. Once tanned, they were washed, rubbed to remove any colouration, and treated with oil such as rapeseed to prevent the skin from drying out too quickly. The skins would then be hung on racks in a dark, warm drying room for between seven and ten days and finally rolled to remove any creases.

Following the tanning, a currier took over, ensuring that the rough, hard and uneven leather was rendered clean, soft, flexible, and waterproof, allowing it to be finished to whatever surface was required by cobblers, saddlers, and other leather workers.

Tanning was a labour-intensive operation, although it’s not known how many men William Lenche employed, probably at the tannery in Deritend. What is known is that like most other wealthy Birmingham traders, he bought property to add to that he’d inherited. In 1487, he took over a house in ‘Moulestreet’, Moor Street, paying the lord of the manor an annual rent of a pound of pepper, an expensive item and signifier of wealth in the Tudor period. Six years later, Lenche purchased an adjoining croft, a small piece of land. This extended to ‘lytyll park street’, Park Street, where later the Lench’s Trust would have almshouses. Lenche himself lived in the house, partly on the site where the Woolpack Hotel would be built. As well as adding to his property in Moor Street, he bought land near the Bull Ring and in 1506, he gained the ‘Calofeldys’ (Callowfields) in Bordesley, then outside Birmingham, from a cousin. These, too, became part of the Trust until the site was purchased by Birmingham Council in 1910 and turned into Callow Fields Park, better known as Garrison Lane Recreation Ground.

A drawing of the Woolpack Hotel in 1911, after it was rebuilt in the late nineteenth

century. In the early 1500s, this was the site of William Lenche’s house.

In 1513, Lenche went on to buy a messuage (house) and lands in Aston, Duddeston, and Bordesley. He followed that with the purchase of a tenement with meadows, leasowes (rough pastures), fields, and other land in Duddeston. This was leased out in 1517, with the document bearing Lenche’s seal, a beautifully-formed monogram \%. The principal witness was Thomas Arden of Park Hall in Castle Bromwich, a distant relative of William Shakespeare’s mother, Mary Arden.

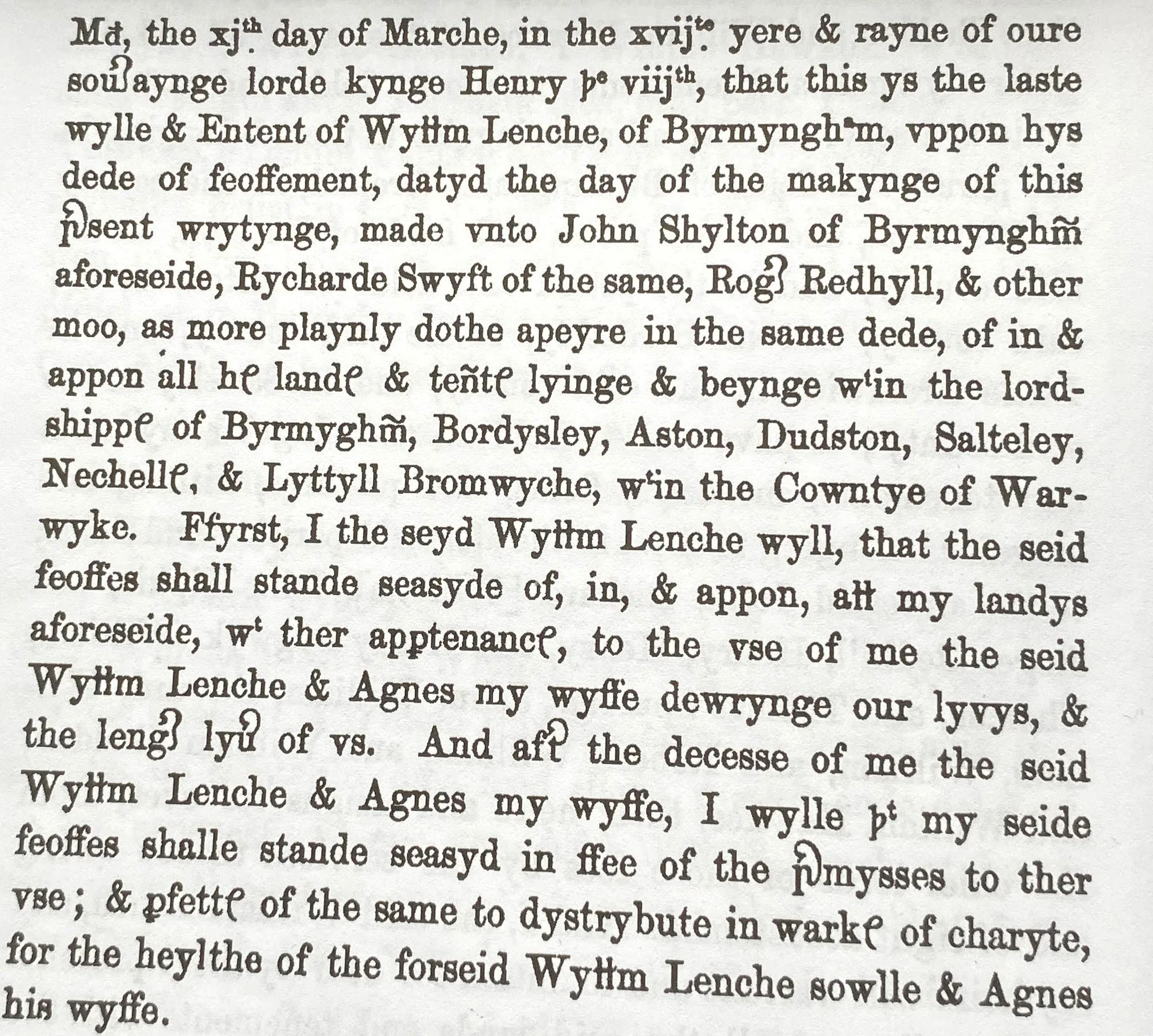

Lenche’s Deed of Enfeoffment, 1525

What kind of man was William Lenche, other than a wealthy and clever businessman? There’s no description of him but it’s apparent that even though he lived in a religious age, his faith was deep and meaningful. His will of 24 March 1525 began as did all others with bequeathing his soul to almighty God, adding to “our blessed seynt Mary, and all the holy company of heaven”. Then he left money to St. Martin’s, where he was to be buried, for making his sepulchre; to the priests present at his committal; to the church’s High Altar; and to the priests who would pray for his soul thereafter. His religiosity was further emphasised by bequests to St. Mary’s Priory and Cathedral in Coventry and to St. Chad’s in Lichfield.

Lenche was as faithful to his friends, giving the same sum to each of his five closest, whilst he was loyal to those who’d helped him. The large amount of 20 shillings each went to his servants, Paynton and Roger Hawkes, who also became a butcher and whose descendants were leading figures in Birmingham for centuries. Two other men were beneficiaries. Nothing is known of them nor of Agnes Swapston, one of two women left money. The second was Margaret Varnam who may have been the widow of another servant. What is clear is that she was a well-off butcher and one of only two women named on the Birmingham Tax Roll of 1547 when she was registered for two payments for land.

Having no children, Lenche bequeathed money to each of his unnamed godchildren and the residue of his estate to his wife, Agnes. Apart from this brief mention and others pertaining to her husband, she’s lost in the shadows of history, although she must have been a capable woman as she was her husband’s sole executor.

Lenche’s will also included a small sum for repairing the pavement of Edgbaston Street. Thirteen days previously, on 11 March 1525, his Declaration of the Intent of Enfeoffment made his generosity and concern for Birmingham and its people even clearer. It stated that after his death and that of his wife, his Trustees should use the income from his estates to distribute in “warke of charyte” for the health of the souls of the couple. Written in English, this was the foundation for the charitable work of Lench’s Trust.

The Deed of Enfeoffment was issued on the same day as the Declaration but in Latin, the language of law. Giving himself as of Birmingham, Lenche grantedto his Trustees:

“… all and singular my lands and tenements, meadows, fields, and pastures, rents and services, with all and singular to them belonging in the parish and field of Birmingham aforesaid, in the county of Warwick, and in the parish and fields of Dudston (Duddeston), in the said county, and in the parish and fields of Aston, in the said county, and in Bordesley in the said county, and in Little Bromwich, in the said county, and in Salteley (Saltley), in the said county; to have and to hold all and singular my lands and tenements, meadows, fields, and pastures, with all and singular belonging to them in the aforesaid parishes and fields …”

There were 19 Trustees in all. Carefully chosen, they were men of substance and influence whose tight connections bring into view some of those responsible for building even stronger the foundations for Birmingham’s later spectacular rise to industrial fame. In so doing, Lenche’s deed gives an invaluable insight into the personal and commercial connections of the ‘movers and shakers’ of Tudor Birmingham, then a town of between 1,000 and 1,400. The first five named were the close friends bequeathed money by Lenche in his will.

William Lenche’s will of 1525.

They were headed by John Shilton the mercer, probably the richest man in Birmingham and its biggest property holder. His wealth was emphasised after his death in 1553 by the inventory of his goods and chattels. With no such document for Lenche, it gives an indication as to the high living standards of Birmingham’s leading citizens. Shilton’s large home had numerous items in the hall, kitchen, back kitchen, tavern, malt chamber, great chamber over the hall, plate room, wife’s chamber, maid’s chamber, high chamber, and two other chambers. Outside there were three tool sheds along with many chattels in wide pastures: 10 oxen; 28 horses; 14 cattle, some with calves; 64 ewes and lambs; 120 hoggerels (young sheep) and wethers (castrated goats and rams); and 14 pigs, little and big.

‘On the ground’ were eight acres of oats in the hay barnes, land that adjoined the modern Great Hampton Row in Hockley. A much bigger estate was the 29 acres of rye, eight of oats, and four of barley at the Byngas. Later owned by King Edward VI School, this was the farm around Shilton’s mansion. The building itself was eventually bought by the banking Lloyds who replaced it with Bingley House. In turn that was knocked down for Bingley Hall, opened in 1850 as the first purpose-built exhibition building in Britain. Today, the ICC covers the spot. As for the Shiltons, they went on to marry into the landed gentry, becoming the lords of Wednesbury and West Bromwich, with one of them achieving the rank of Solicitor-General to Charles I.

Richard Swyft was the second of Lench’s Trustees. His family was mentioned in the Birmingham rental of 1296, whilst it was also well established in Yardley, then in Worcestershire. A witness to several other important documents, he was amongst the highest taxpayers for land in Birmingham in 1547. Roger Redhyll was third. Another prosperous landholder, his father left him the substantial sum of £20 in 1522. The rest of his inheritance gives another insight into the possessions of Birmingham’s wealthiest men. He received one of his father’s three goblets; six silver spoons; a feather bed with all things pertaining to it; a brass pot; 12 pewter vessels; a basin with a laver (wash basin); and a chafing dish (a metal cooking pan on a stand and heated with charcoal in a brazier for gentle cooking away from direct flames). These were all expensive and valued goods.

As supervisor of his father’s will, Redhyll was joined by Lenche and Shilton. One of the three witnesses was John Hypkys, who was the fourth named of Lenche’s Trustees. It seems he was the father of another John Hypkys, an ox shoer, a highly-skilled man with a home and blacksmith’s shop in Winson Green. His prosperity was made clear by his bequests of the substantial amounts of £30 each to his son and daughter. William Symondes was the fifth and last of Lench’s friends named in both his will and deed of gift. A cousin of Shilton, he held land and property but classed himself as a gentleman, earning enough from rents not to have to engage in trade. On other documents, he was given as an armiger, someone with armorial bearings, a counsellor, and serjeant-at-law and judge of South Wales. Symonds was a powerful and determined man and would be the leading figure in effectively saving Lench’s Trust in 1540.

William Lenche’s

Declaration of the

Intent of Feoffment,

11 March 1525,

written in English

and naming only

John Shylton,

Richard Swyft, and

Roger Redhyll from

amongst the feoffees.

Four other Trustees were amongst Birmingham’s trading elite. William Sheldon was a tanner and though not as wealthy as John Shilton, he was a most prosperous man. Dying in 1551, he left over £6 to one daughter towards her marriage; his gown furred with black lamb’s wool to one son-in-law; and his best gown to another. Amongst other expensive clothing, he gave his five sons his sleeveless jacket and doublet with fustian sleeves, best doublet of satin, best pair of hose, and best doublet stacked with velvet.

An ironmonger, William King was one of the loving brethren and friends of another Trustee, William Colmore the elder. A rich mercer, Colmore’s family would become the most powerful in Tudor Birmingham, recalled in Colmore Row and the adjoining streets. With roots in the Solihull area, Colmore the elder wasn’t mentioned in the 1524-25 tax record but was amongst the highest payers in the 1543 Lay Subsidy, exceeding even Shilton and Symonds. He died in 1566 and was remembered by a slab in St. Martin’s Church upon which he was shown in a long civilian’s gown, with hanging sleeves – each of which had slits at the upper part and through which the arms passed. That disappeared and today one of the oldest memorials in the church is a canvass of dark wood high on the south transept wall. It was erected in 1612 by William Colmore the younger in memory of his parents and shows the ‘Grim Reaper’ – a seated skeleton holding a scythe.

The oldest of eight sons, this William was a witness to Lenche’s Deed of Enfeoffment and benefited the most from the will of his father the Trustee, whose riches were emphasised by his bequests of 100 marks to each of his seven younger sons. A mark was the equivalent of two thirds of a pound and this was boosted by inheritances of property. As for the older Colmore’s five daughters, they were each given £100. These were enormous amounts considering that as late as the turn of the twentieth century, the poverty line for a modest family of four was about £1 a week. Colmore the elder also passed on gold, silver, and jewels, and, importantly, added to Lench’s Trust with his own charitable bequest.

The fourth Trustee of abundance was William Phillips, whose family had land in Erdington and Bordesley and whose ancestor of the same name was recorded as renting a property from Birmingham’s lord of the manor in 1296. His descendants did exceptionally well and in 1426, a John Phelyps was described as a chalonnere, someone who sold bedding.

Colmore Row in the 1950s, one of several streets recalling the Colmore family, the

most powerful in Tudor Birmingham and influential as Lench’s Trustees. The building

on the left, on the corner with Newhall Street, was later demolished and replaced by a

tower block. The buses in the background are by St. Phillip’s Churchyard.

Like the Shiltons, the family moved away from trade and into landholding and property, with William Phillips featuring prominently in the great 1553 Survey of Birmingham. He freely held a house in ‘Dygbathe’ with a croft, and two fish ponds, land and buildings in Park Street. This was supplemented by the rent of land and buildings in Molle (Moor) Street, New Street, High Street, Dale End, and elsewhere. One intriguing rental related to a pasture called Bennetts Hill, for which William paid one rose at the feast of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist.

His son, Ambrose, inherited the family lands and was later described as a gentleman living in Walsall. No longer having to work, he’d entered the gentry. By the early seventeenth century, the Phillipses owned most of the land and dwellings they’d once rented, as well as much of New Street and the Bull Ring. The last of the family’s direct line was Robert Phillips of Newton Regis near Tamworth. It was his wife, Elizabeth, who gave Horse Close on Bennetts Hill for the building of St. Philip’s Church. Consecrated in 1715, it’s now Birmingham Cathedral, carrying the name of a family deeply connected to Birmingham and the Lench’s Trust. After Robert Phillips, his property passed through marriage to Theodore William Inge of Thorpe Constantine, recalled in Inge Street and Thorp Street.

Looking along Phillips Street, named after the family of one of Lench’s Trustees, to

Moor Street. The old Market Hall is to the right and the Fish Market to the left.

The street and buildings were swept away in the post-1945 redevelopment of the

Bull Ring.

The remaining Trustees included men connected to Lenche’s five close friends. Henry Shilton was Symond’s brother-in-law and a relative of John Shilton; William Hawkes was the father of Lenche’s servant Roger Hawkes; and John Swyft was a relation of Richard Swyft. They were joined by William Paynton, Lenche’s servant; Henry Sygwyk, related to an executor of Lenche’s will and the owner of the Bull Tavern in Chapel Street, afterwards Bull Street; Thomas Spurriar, a landholder; Edward Pepwell, one of a family long connected with that of Lenche in Duddeston; William Askryk, a newcomer to Birmingham who was a landholder and active in public affairs; and Thomas Wygstyd and Robert Goldson, about whom nothing is known.